Tutorials

Binary Search

Suppose we wish to know whether or not a particular value is stored in an array of integers. Consider the following array:

- With just seven elements is very easy to just scan the array looking for a match on a particular value.

- This is the standard brute-force approach which would require, at most, seven comparisons1)

- The brute-force search is an \( O(n) \) algorithm, where \( n \) is the size of the array, since we must visit each element in the array.

- If doing the comparisons is very expensive, or if we have a large array, we may be motivated to find a more efficient way of searching.

- To keep you sufficiently motivated, please pretend that only one person in the world knows how to compare integer values, and that person lives at the top of Mount Milikawi. Unfortunately, she will only compare two integer values and provide you with an answer if you prepare her favorite meal consisting of Huhu grubs boiled in sugar cane oil. To make matters worse, she doesn't have much of an appetite so you can only get her to do three comparisons a day... and that assumes you catch her before she snacks on some Kaolin and ruins her appetite.

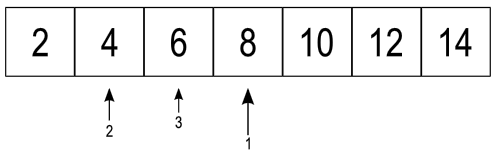

- Suppose we wanted to know if 6 was in the array.

- Because the array is sorted, we could begin by comparing 6 to middle element.

- Since 6 < 8, we know that if 6 is in the array, it will be in the first half of the array.

- Next we'll compare 6 with the element in the middle of the first half of the array (the 4).

- Since 6 > 4, we know that if 6 is in the array, it will be between the 4 and the 8.

- This approach is known has binary search.

- Generally speaking it works like this:

- Begin with the entire array.

- Split the array into two parts (this is where the binary in binary search comes from).

- Compare what we are looking for with the element in the middle of the two parts.

- If it matches, we are done.

- If we are looking for something small, then we eliminate the second part from consideration and repeat from step 2 with just the first part.

- If we are looking for something larger, then we eliminate the first part from consideration and repeat from step 2 with just the second part.

- This turns out to be very efficient because each comparison allows us to rule out half of the remaining elements from consideration.

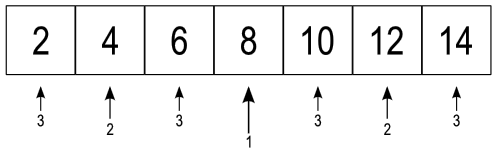

- The following figure shows the number of comparisons needed to find any value in the array:

- Does it take more comparisons than three if we are looking for a value not in the array?

- Suppose we were looking for 5, we would compare with 8, then 4, then 6 and at that point we would know it wasn't in the array because there are no values between 4 and 6.

- Consider 9: Compare with 8, 12, and 10 to discover that it is not in the array since there are no elements between 8 and 10.

- Consider 58: Compare with 8, 12, and 14 to discover that it is not in the array since 14 is the biggest value in the array.

- In fact, it will always take just three comparisons to determine that a value is not present in an array of seven elements.

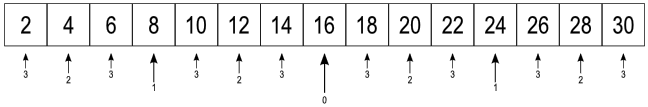

- The amazing thing is that if we roughly double the number of elements in our array, it only takes one more comparison, at most, to answer the "contains" question.

- Here is the proof by picture:

- An array with one element requires a maximum of one comparison

- An array with three elements requires a maximum of two comparisons

- An array with seven elements requires a maximum of three comparisons

- An array with fifteen elements requires a maximum of four comparisons

- ...

- An array with \( 2^n - 1 \) requires a maximum of \( n \) comparisons (for all non-negative values of \( n \))

Time Complexity of Binary Search

- If you paid attention in math class you probably heard a definition for the logarithm that went something like this: "The logarithm of a number to a given base is the exponent by which the base must be raised to produce that number."

- Since we are talking about binary, let's consider a given base of 2.

- Specifically, the base 2 logarithm of \( x \) is the exponent by which two must be raised to produce \( x \) , i.e., if \( y = \log_2 x \) , then \( y \) must satisfy \( 2^y = x \).

- Applying this to what we just learned about the maximum number of comparisons needed to do a binary search, we can say:

| Number of elements | Maximum Required Comparisons |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 7 | 3 |

| 15 | 4 |

| 31 | 5 |

| 63 | 6 |

| \( 2^n - 1 \) | \( n \) |

| \( n \) | \( \log_2 n \) |

We get the last line by taking the \( \log_2 \) of both entries in the second to the last line since \( \log_2 (2^n - 1) \approx \log_2 2^n = n \).2)

It's worth noting that if the size of the array is between \( 2^{n-1} - 1 \) and \( 2^n - 1 \) it still may take up to \( \log_2 n \). We can more correctly say that the maximum number of comparisons required for an array of size \( n \) is \( \log_2 n \) rounded up to the nearest integer.

Last modified: Monday, 29-Jul-2024 06:54:25 EDT